Archive

Griffiths’ century on the high seas, silver screen, and back again

August 21, 2013 · 0 Comments

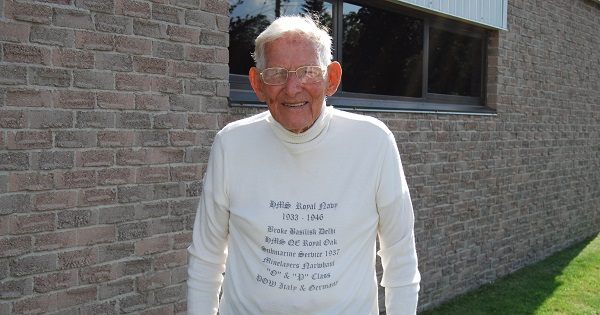

(Aurora’s Allen Griffiths, pictured above at the Royal Canadian Legion wearing a shirt outlining his military service, will turn 100 on Monday, August 26. Auroran photo by Brock Weir)

By Brock Weir

Swathed with scarves around his head and neck, soot strategically placed on his face and arms, and brandishing a sword like a self-described “vagabond”, Allen Griffiths found himself on shipboard amongst the enemy.

It was the late 1930s, the Spanish Civil War was still raging, the Germans were interfering, but the Second World War had yet to break out.

As a stoker on board the ship, he clearly remembers popping out of his hold and exclaiming, “Cookie, have you heard the buzz?”

Undoubtedly it’s a quote that would not be out of place in the middle of a 1930s sea battle and indeed the ship was going down. Water was coming on board and his fellow seamen were quickly jumping overboard to save themselves.

They were not, however, in danger just yet.

While Mr. Griffiths was indeed a stoker on board the ship, actively serving with the navy, this was all in good fun. The filmmakers who had drafted him and many of his other shipmates into “extra” roles in the 1937 film “Our Fighting Navy” (later re-titled “Torpedoed!”) had taken over the HMS Royal Oak and turned it into one of the “enemy” ships in the film.

To create the illusion of the ship sinking into the abyss, director Norman Walker had all the guns moved to one side of the ship to create a natural tilt. That’s when the magic happened, joined by stars Richard Cromwell, Hazel Terry, and Noah Beery (brother of Wallace).

Their names may have started to fade slightly into the Hollywood ether, but memories of the filming are still vivid for Mr. Griffiths, an Aurora resident who celebrates his 100th birthday this Saturday.

“When we got cleaned up after the filming, they kept me on for a couple of weeks,” says Mr. Griffiths. “I remember the guy who was looking after the uniforms and costumes and in the evenings he was supplying the girls with silk stockings. They had just come out then and were very rare.

“We were all going back to the hotel and there was Beery going up the stairs, drunk as a skunk with these two girls. The fellow I was working with said, ‘there go my stockings!’”

Memories around the filming of “Our Fighting Navy” are some of the happier ones associated with the HMS Royal Oak. Shortly after he moved onto another ship, the Royal Oak was torpedoed by the Germans in the early days of the Second World War, killing 833 people on board.

“She never fired a g–damned shot,” says Mr. Griffiths. “She was lying up in the north of Scotland supposed to be safe as nobody could get in because of the rocks and the sand, but that all disappeared over the years because nobody had surveyed it. The German submarine came in just as smooth as you like at midnight, fired five or six torpedoes on it and she went down all hands.”

The name of the HMS Royal Oak has pride of place on a special shirt Mr. Griffiths wears to this day. What he calls his “personal Mona Lisa” as there is only one shirt like it in the world, it lists all the ships, submarines and vessels he served on over his 13-year stint with the Royal Navy.

While their German and Italian counterparts ensured each of these vessels met their own grizzly ends, they were unable to get the better of Mr. Griffiths.

He was born on the border of England and Wales in 1913, less than a year before the outbreak of the First World War.

His father was a policeman who served in the Boer War, while his mother served as a nurse, treating some of the names that would have filled the newspapers of the day. When war eventually broke out in Europe, it was a break felt very much on the home front.

His father was back in service, heading overseas with his wife, back in her nursing uniform. While they served, their sons were taken into an orphanage under the auspices of the local police authority where they were treated to conditions which were commonplace at the time, but would be shocking to today’s society.

“I was a bed wetter,” he says with a laugh. “This Mrs. Murray used to come to us, get me by the hair and shove my nose it, then lock me in a cupboard while she made the beds. I got so scared of going into bed that I would lay on the floor. I would get so cold, I would have to jump back into bed and then wet the bed again.”

Relief finally came with the Armistice in 1918. When peace was declared, he remembers celebrating by getting dressed up as a soldier, complete with his arm in his sling, to parade for Princess Marie Louise of Schleswig-Holstein, one of Queen Victoria’s more eccentric granddaughters who was visiting the village.

Lining up to meet the dignitary, the Princess presented each of them a prayer book, which remained a prized possession for decades.

Finally, their mother came to pick them up, but she was not accompanied by their father. He was felled on the field in 1916.

“When he was shot, they sent his clothes home in a coffin,” says Mr. Griffiths. “Three or four coins fell out of his pocket. I still hang onto the farthing. The penny with the bullet hole in it was given to my brother, Jack.”

Settling back with his family, Mr. Griffiths’ story turns to village life, heading to his grandfather’s tenant farm, which his family had on a 99 year lease from the local “squire.” From cleaning the squire’s boots, he eventually rose through the ranks to become a groom, preparing horses for the local hunts.

They are iconic scenes, with the young groom preparing the horses while generations of ladies prepare the sandwiches, cakes, beer and cider for the well-heeled men and women riding.

With a twinkle in his eye, he recalls greeting Lady Lubbock, an old acquaintance and scion of the Bonham Carter Family, who crossed paths with him on a very hot horse.

“Lady Lubbock had a big black horse and I knew her well,” he says. “I said, ‘Lady Lubbock, your horse is sweating pretty bad, can I give him a rubdown?’ She said, ‘So would you sweat if you were between my legs for two hours!”

Obviously that left a lasting impression on a 14-year-old boy, but those halcyon days came to an end with the death of the squire. Looking for work, he got a job as an errand boy for a wholesale grocer, eventually delivering sugar throughout the Welsh valleys before he joined his young friends in looking for work with the Navy.

Initially starting work as a fitter, he wasn’t quite tall enough for the marines but found good paying work as a stoker below deck. It paid well, but it also required a longer commitment – 12 years rather than the customary five.

It was at a time when Hitler wasn’t yet seen as the threat he would soon be.

After one of his first missions, he and his crew were greeted back in Plymouth in a public celebration by King George V, accompanied by the Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII and Duke of Windsor), who inspected the ranks. It was a very big deal and looking back, he suspects it was all part of the propaganda machine to face the challenges ahead.

And as someone who had just finished laying a minefield on the seabed with his crew as Neville Chamberlain triumphantly flew back in England waving a piece of paper declaring “peace in our time”, there were certainly many challenges awaiting Mr. Griffiths.

Next week, The Auroran’s interview with Mr. Griffiths will continue with a closer look at his service during the war, and his Canadian journey, which began in 1951.